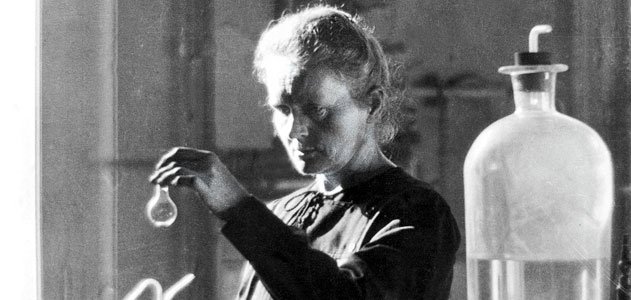

Marie Curie is probably one of the most famous female scientist, and rightly so. She is definitely a badass female scientist we should all aspire to be like. Plus, I don’t want to sound biased, but she also got her degrees in Physics, making her one of the most renowned female physicist in history, and I like to consider myself an amateur physicist. So, here is a [not-so] brief summary of why she is this week’s Badass Female Scientist, and role model to anyone out there with a passion.

Marie Curie was born in Warsaw, Poland, November 7, 1867, which was, at that time, under Russian rulership. Marie’s family held nationalistic pride in Poland, rather than Russia, so she chose to move to Cracow, which was at that time under Austrian rule. Her parents were both teachers, so she was raised with the understanding of how important learning was. She followed her father’s footsteps in studying Physics and Mathematics. However, times were extremely hard for her family. Due to their Polish heritage, it was difficult for Marie’s father to find a job, and many of the universities in Warsaw wouldn’t accept female students. So, Marie and her sister spent about three years working in the factories and saving up enough money to move to Paris. Her dream came true when she was 24 years old, as she enrolled in Sorbonne University in Paris, where she excelled in her physics courses. Pierre Curie took note of her academic excellence, and accepted Marie to work in his lab at the Paris Municipal School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry. Though he was 10 years her senior, their relationship deepened and he convinced her to remain in Paris, as she convinced him to submit his thesis and finally earn his doctoral degree.

Marie Curie was born in Warsaw, Poland, November 7, 1867, which was, at that time, under Russian rulership. Marie’s family held nationalistic pride in Poland, rather than Russia, so she chose to move to Cracow, which was at that time under Austrian rule. Her parents were both teachers, so she was raised with the understanding of how important learning was. She followed her father’s footsteps in studying Physics and Mathematics. However, times were extremely hard for her family. Due to their Polish heritage, it was difficult for Marie’s father to find a job, and many of the universities in Warsaw wouldn’t accept female students. So, Marie and her sister spent about three years working in the factories and saving up enough money to move to Paris. Her dream came true when she was 24 years old, as she enrolled in Sorbonne University in Paris, where she excelled in her physics courses. Pierre Curie took note of her academic excellence, and accepted Marie to work in his lab at the Paris Municipal School of Industrial Physics and Chemistry. Though he was 10 years her senior, their relationship deepened and he convinced her to remain in Paris, as she convinced him to submit his thesis and finally earn his doctoral degree.

Two mysterious discoveries led Marie to what she would be known for. First, Wilhelm Roentgen had discovered that certain rays (X-rays) could travel through solid and flesh. Second, Henri Becquerel had discovered that minerals containing uranium gave off these x-rays, but at a small degree. Marie, needing a topic to earn her doctoral degree, chose to focus on these uranium rays. Though her now husband, Pierre, was a professor, he still only had a small and old lab room. But, Marie needed a place to work, so she chose one of his storerooms to begin her research. She started off by examining different compounds that contained uranium, and found that the intensity of the rays depended solely on the amount of uranium in the compound. This puzzled Marie, as typically the properties of compounds change accordingly to how the compound is treated. She also discovered that other elements could give off these rays, coining the behavior as “radioactivity.” As she looked through more and more compounds that gave off radioactivity, she discovered that one particular compound, then known as “pitchblende,” gave off more radioactivity than initially predicted by the amount of uranium in it. Thinking that perhaps they had stumbled upon a new element, one that is extremely radioactive, Pierre set aside his own research to help Marie expedite the research. Instead of just one element, the Curies had actually discovered two new elements: Polonium (named after Poland) and Radium (from the Latin word for ray). To isolate these two elements they needed much more space, and were forced into working at a nearby shed. At that time, they discovered that radium could actually injure human flesh by the sheer amount of energy it expelled. While Marie had lost 20 lbs. and Pierre was often exhausted and in pain, they continued on refusing to believe that radium could be very harmful. With these new discoveries, however, industries began investing more into the Curie’s research, and their lab was finally able to grow. Most of the money went straight to the research, and the Curies had to take on more teaching positions to be about to cover basic household expenses. All the while, Marie was able to complete her doctoral thesis and in 1903 she became the first woman to receive a doctorate in France. Furthermore, the Curies were also awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, Marie being the first woman to win a Nobel Prize. Unfortunately, the luck was short-lived as Pierre was ran over by a horse-drawn wagon and killed instantly in 1906. Because of his death, Marie was appointed his position, making her the first female professor at the university. Refusing to let her husband’s work be forgotten, Marie and a few of her scientist friends were able to gather enough funds to establish the Radium Institute, where she would head the laboratory.

However, things did not get any easier for Marie. She was now a widow and mother of two, working towards establishing the Radium Institute, working as a professor to the university, and once a week she taught science to her daughter’s class. She also had to deal with petty drama between her and Paul Langevin, one of Pierre’s students who had become infatuated with her. Pulling herself together, she was still able to win a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her discoveries, but the workload was obviously too much and she collapsed from kidney problems and depression. But, the Radium Institute was about to open its doors in 1914 and she was excited to start her work. August of 1914, times took a turn for the worst. Germany had invaded France and much of Marie’s staff had enlisted in the war. So, Marie began moving her focus onto how X-rays could benefit the soldiers on the fields. She was able to set up 20 mobile X-ray stations and 200 stationary stations for doctors to use on wounded soldiers. Her efforts were applauded after the war and she was given enough money in funds to run her Radium Institute without problem, which is what she did until her demise in 1934. Marie Curie died from aplastic anemia, a blood disease caused by exposure to high amounts of radiation. She was buried by Pierre and in 1995 both of their bodies were transferred to the Pantheon in Paris.

However, things did not get any easier for Marie. She was now a widow and mother of two, working towards establishing the Radium Institute, working as a professor to the university, and once a week she taught science to her daughter’s class. She also had to deal with petty drama between her and Paul Langevin, one of Pierre’s students who had become infatuated with her. Pulling herself together, she was still able to win a second Nobel Prize in Chemistry for her discoveries, but the workload was obviously too much and she collapsed from kidney problems and depression. But, the Radium Institute was about to open its doors in 1914 and she was excited to start her work. August of 1914, times took a turn for the worst. Germany had invaded France and much of Marie’s staff had enlisted in the war. So, Marie began moving her focus onto how X-rays could benefit the soldiers on the fields. She was able to set up 20 mobile X-ray stations and 200 stationary stations for doctors to use on wounded soldiers. Her efforts were applauded after the war and she was given enough money in funds to run her Radium Institute without problem, which is what she did until her demise in 1934. Marie Curie died from aplastic anemia, a blood disease caused by exposure to high amounts of radiation. She was buried by Pierre and in 1995 both of their bodies were transferred to the Pantheon in Paris.

So, what did we learn from Marie Curie? Not only did she have to work for her own money to support her education, but all throughout her life she struggled for recognition because she was a female. Regardless, she was able to score two Nobel Prizes, become the first female professor at her university, and become the first female to receive a doctorate in France. However, her and Pierre had to work together. He didn’t see her as a “female lab tech,” but rather as the ingenious physicist she was. They supported each other until death, while raising a family. If thats not a relationship goal, I don’t really know what is.